During my visit to Seville last week, I went to a temporary art exhibition titled: TERRITORIES – Latin American Art in the Jorge M. Pérez Collection, at the CAAC, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporaneo, based at the Monastery of the Cartuja (Charterhouse).

The venue has historical relevance on its own. Built as a monastery in the 15th century, it was vacated in the 19th century and acquired by an Englishman, Charles Pickman, to be used as a ceramics factory until late in the 20th century. In 1997, the Carthusian Monastery became the headquarters of the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporaneo, or CAAC. However, despite the fantastic venue where the exhibition is based, the museum could benefit from clearer signage or directions for visitors. After purchasing tickets, we had to explore the building to find the entrance to the exhibition. Unfortunately, there were no signs or banners to guide us.

Seville’s historical significance as a river port and its role in transatlantic trade bring valuable context to the exhibition’s location. This exhibition contributes to the cultural landscape of Seville and its historical connections with Latin America.

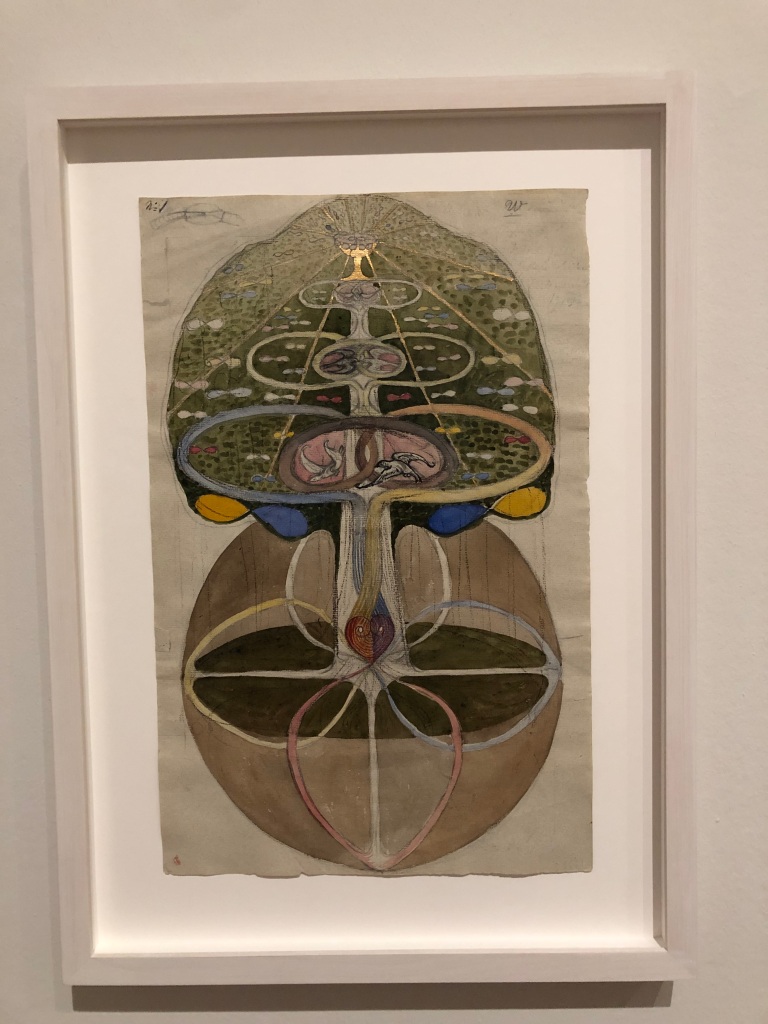

The exhibition showcases a selection of works by more than 50 contemporary Latin American artists. Curated by the topics on which these artists choose to focus with their work, it highlights the socio-cultural plurality of Latin America and their concerns in relation to politics, borders, inequality, ethnicity, and integration with nature, among others. Including an abstract art room that is a bit more difficult to categorize in relation to these themes.

The collection on display belongs to Jorge M. Pérez (1949), known for his association with one of the most prestigious art institutions in the United States, the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM). Pérez was born in Argentina to Cuban parents and raised in Colombia. A resident of Miami since 1968, he is an entrepreneur and philanthropist who began collecting art at a young age to maintain a connection with his Hispanic American roots and cultural heritage.

Upon entering the art show, the first artworks that greeted us were from ‘Colour is my business, 2012-2016’ by Alexander Apostol (Venezuela, 1969), a series of 12 photographs identifying the colours of Venezuelan political parties. It reminded me of the vibrant works of Brazilian artists like Hélio Oiticica – a joyful way to start an art show.

In the first room, there is also a floor art installation by Maria Nepomuceno (Brazil, 1973), incorporating weaving, ceramics, wood, and glass. It establishes a relationship between the body and nature, reflecting on memory and promoting an encounter between past, present, and future.

Another piece that caught my attention was ‘Dead Rats Don’t Open Their Mouths, 2014’ by MORIS (Israel Meza Moreno) (Mexico, 1978). His work offers a glimpse into everyday urban culture, integrating diverse social codes of the street.

Another room titled ‘Cartographies of the Spirit’ explores territorial intersection and socio-political boundaries, with works like Mateo Lopez’s (Bogota, Colombia, 1978) blackboard ‘Board, 2014,’ reflecting on identity and memory.

In the central corridor, ‘Vertical 19’ by Claudia Andujar (Switzerland, 1931) portrays the Yanomamis in the Catrimani River basin in Brazil, showing their integration with nature.

A separate room showcases ‘Eu, mestizo, 2017’ by Jonathas de Andrade (Brazil, 1982), exploring mestizaje, ethnicity, and class in Latin America. Andrade dismantles the myth of racial democracy in Brazil with series of pictures of men and women in contrast with the adjectives extracted from the book ‘Race and Class in Rural Brazil’ published in the 1950s by Columbia University and the UNESCO, placing racial issues in a historical perspective that is far from being resolved.

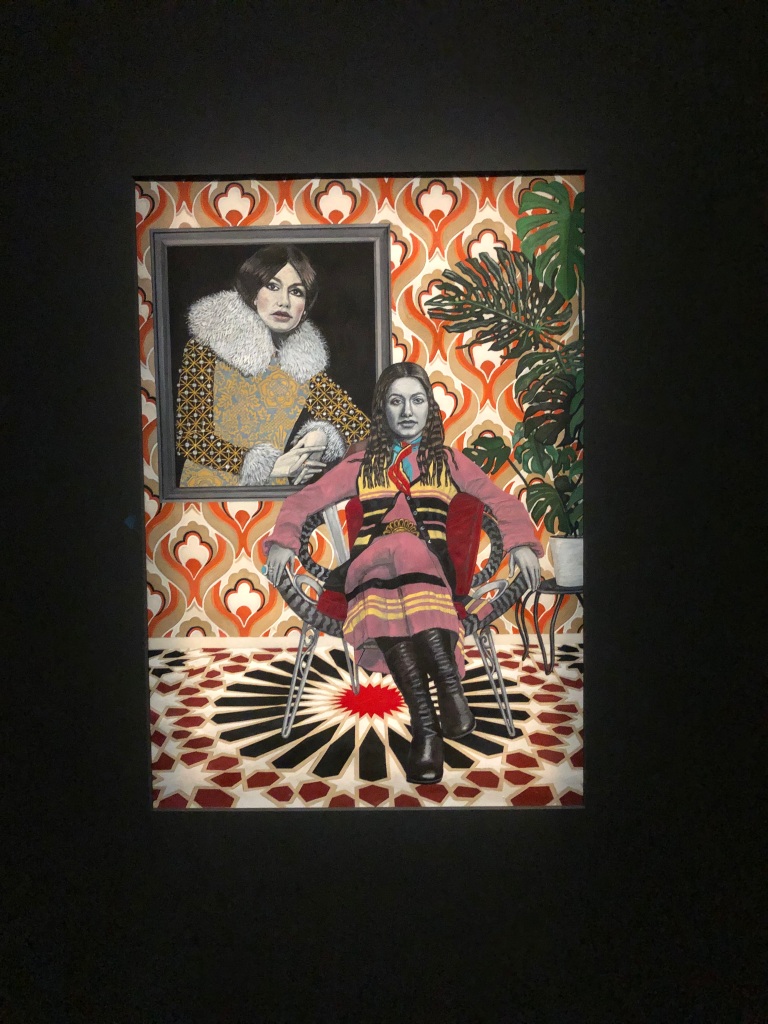

The room titled “Me, Myself and I” was dedicated to gender and identity, two intertwined themes as well as objects of activism and discussion in Latin America. Herman Bas (Miami, 1978), for instance, addresses issues of identity and belonging. Bas challenges conventional gender expectations and decontextualizes objects to provoke reflection.

‘Panorama Catatumbo, 2018’ by Nohemi Perez (Colombia, 1964), a charcoal-on-fabric work, depicts territories affected by unequal development and internal conflicts.

Another artwork that caught my attention was ‘Mantle I’ by Alice Wagner (Lima, Peru, 1974) that focuses on power and colonization where she combines different medium and techniques as a reflection and a confrontation between indigenous and European cultures and how these interactions have influenced Peruvian identity. In the same room, I found also outstanding the work by Claudia Coca (Lima, 1970) where she uses drawings simulating National Geographic covers, which from the artist’s point of view addresses scientific, cultural and historic topics that insist on the wild, exotic and distant in contrast to the West. The myth of the Other and its alien nature is clearly reflected here.

In one of the final rooms titled ‘Memory and Resistance,’ I encountered the works of some of the most renowned artists featured in this exhibition. Doris Salcedo (Bogota, Colombia, 1958) gives voice to the lives lost and forgotten due to the war on drug trafficking, ensuring they remain in collective memory by displacing everyday objects. In this instance, I observed a chair laden with cement.

Ana Mendieta (Cuba, 1948 – USA, 1985) presents a series of photographs exploring the connection between the body and nature through her performances and sculptures, drawing attention to violence against women in the USA. Meanwhile, Tania Bruguera (Cuba, 1968) addresses the lack of expression and freedom with two pieces showcased in this exhibition, which can also be viewed below.

Finally, ‘Statue of Liberty falling, 1983’ by Argentinian artist Marta Minujin (Buenos Aires, 1943) was created to commemorate the restoration of democracy in Argentina.

The exhibition effectively organizes artworks around key themes concerning Latin American artists, exploring issues such as racism, ethnicity, class, and borders. It showcases brilliant works by highly recognized artists, shedding light on important cultural and political issues affecting Latin America.

Furthermore, in the 16th century, Seville was the main gateway to the transatlantic trade of the Spanish Empire, thanks to its position as the only river port in Spain and being one of the largest cities in Western Europe. Therefore, I consider choosing to host this exhibition in Seville meaningful, as it revitalizes the historical role of the city as a point of connection and highlights the deep cultural ties between Spain and Latin America.

La riqueza del arte latinoamericano

TERRITORIOS: Arte Latinoamericano Contemporáneo en la Colección de Jorge M. Pérez

2 de marzo – 1 de septiembre de 2024

CAAC, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Sevilla, España

Durante mi visita a Sevilla la semana pasada, existí a una exposición de arte temporal titulada TERRITORIOS – Arte Latinoamericano en la Colección de Jorge M. Pérez, en el CAAC, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, ubicado en el Monasterio de la Cartuja (Monasterio de Santa María de las Cuevas).

El lugar tiene relevancia histórica por sí solo. Construido como monasterio en el siglo XV, fue desamortizado por Mendizábal en el siglo XIX y adquirido por un inglés, Charles Pickman, para ser utilizado como fábrica de cerámica hasta finales del siglo XX. En 1997, el Monasterio Cartujo se convirtió en la sede del Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo o CAAC. Sin embargo, a pesar del fantástico lugar donde se basa la exposición, el museo podría beneficiarse de una señalización o indicaciones más claras para los visitantes. Después de comprar las entradas, tuvimos que explorar el edificio para encontrar la entrada a la exposición. Desafortunadamente, no había señales ni pancartas que nos guiaran.

La relevancia histórica de Sevilla como puerto fluvial y su papel en el comercio transatlántico aportan un contexto valioso a la ubicación de la exposición. Esta exposición contribuye al paisaje cultural de Sevilla y sus conexiones históricas con América Latina.

La exposición presenta una selección de obras de más de 50 artistas latinoamericanos contemporáneos. Comisariada por los temas en los que estos artistas eligen enfocarse con su trabajo. Resalta la pluralidad sociocultural de América Latina y sus preocupaciones en relación con la política, las fronteras, la desigualdad, la etnicidad y la integración con la naturaleza, entre otros. Incluyendo una sala de arte abstracto un poco más difícil de categorizar en relación con estos temas.

La colección que se muestra pertenece a Jorge M. Pérez (1949), conocido por su asociación con una de las instituciones de arte más prestigiosas de los Estados Unidos, el Museo de Arte Pérez de Miami (PAMM). Pérez nació en Argentina de padres cubanos y se crió en Colombia. Residente de Miami desde 1968, es un empresario y filántropo que comenzó a coleccionar arte a una edad temprana para mantener una conexión con sus raíces hispanoamericanas y su herencia cultural.

Al ingresar a la exposición de arte, las primeras obras que nos recibieron fueron de ‘Colour is my business, 2012-2016’ de Alexander Apostol (Venezuela, 1969), una serie de 12 fotografías que identifican los colores de los partidos políticos venezolanos. Me recordó a las obras vibrantes de artistas brasileños como Hélio Oiticica, una forma alegre de comenzar una muestra de arte.

En la primera sala, también hay una instalación de arte en el suelo de María Nepomuceno (Brasil, 1973), que incorpora tejidos, cerámica, madera y vidrio. Establece una relación entre el cuerpo y la naturaleza, reflexionando sobre la memoria y promoviendo un encuentro entre pasado, presente y futuro.

Otra pieza que llamó mi atención fue ‘Las ratas muertas no abren la boca, 2014’ de MORIS (Israel Meza Moreno) (México, 1978). Su trabajo ofrece una visión de la cultura urbana cotidiana, integrando diversos códigos sociales de la calle.

Otra sala titulada ‘Cartografías del Espíritu’ explora la intersección territorial y los límites socio-políticos, con obras como ‘Tablero, 2014,’ de Mateo López (Bogotá, Colombia, 1978), reflexionando sobre la identidad y la memoria.

En el pasillo central, ‘Vertical 19 – da serie Marcados, 1983’ de Claudia Andujar (Suiza, 1931) retrata a los Yanomamis en la cuenca del río Catrimani en Brasil, mostrando su integración con la naturaleza.

Una sala aparte presenta ‘Eu, mestizo, 2017’ de Jonathas de Andrade (Brasil, 1982), explorando el mestizaje, la etnicidad y la clase en América Latina. Andrade desmonta el mito de la democracia racial en Brasil con una serie de imágenes de hombres y mujeres en contraste con los adjetivos extraídos del libro ‘Raza y Clase en Brasil Rural’, publicado en la década de 1950 por la Universidad de Columbia y la UNESCO, situando los problemas raciales en una perspectiva histórica que está lejos de ser resuelta.

La sala titulada “Yo, mi, me, conmigo” estuvo dedicada al género y la identidad, dos temas entrelazados y objetos de activismo y discusión en América Latina. Herman Bas (Miami, 1978), por ejemplo, aborda temas de identidad y pertenencia. Bas desafía las expectativas de género convencionales y descontextualiza objetos para provocar reflexión.

‘Panorama Catatumbo, 2018’ de Nohemi Pérez (Colombia, 1964), una obra de carbón sobre tela, representa territorios afectados por un desarrollo desigual y conflictos internos.

Otra obra que llamó mi atención fue ‘Manto I’ de Alice Wagner (Lima, Perú, 1974), que se centra en el poder y la colonización, donde combina diferentes medios y técnicas como reflejo y confrontación entre las culturas indígenas y europeas y cómo estas interacciones han influenciado la identidad peruana. En la misma sala, también encontré destacado el trabajo de Claudia Coca (Lima, 1970), donde utiliza dibujos que simulan portadas de National Geographic, que desde el punto de vista del artista abordan temas científicos, culturales e históricos que insisten en lo salvaje, exótico y distante en contraste con Occidente. El mito del Otro y su naturaleza ajena se refleja claramente aquí.

En una de las últimas salas titulada ‘Memoria y resistencia’, me encontré con las obras de algunas de los artistas más reconocidas de esta exposición. Doris Salcedo (Bogotá, Colombia, 1958) da voz a las vidas perdidas y olvidadas debido a la guerra contra el narcotráfico, asegurando que permanezcan en la memoria colectiva mediante la displaciaón de objetos cotidianos. En este caso, observé una silla cargada de cemento.

Ana Mendieta (Cuba, 1948 – EE. UU., 1985) presenta una serie de fotografías que exploran la conexión entre el cuerpo y la naturaleza a través de sus performances y esculturas, llamando la atención sobre la violencia contra las mujeres en Estados Unidos. Mientras tanto, Tania Bruguera (Cuba, 1968) aborda la falta de expresión y libertad con dos piezas presentadas en esta exposición, que también se pueden ver a continuación.

Finalmente, ‘Estátua de la Libertad cayendo, 1983’ de la artista argentina Marta Minujín (Buenos Aires, 1943) fue creada para conmemorar la restauración de la democracia en Argentina.

La exposición organiza eficazmente las obras de arte en torno a temas clave relacionados con los artistas latinoamericanos, explorando temas como el racismo, la etnicidad, la clase y las fronteras. Muestra obras brillantes de artistas altamente reconocidos, arrojando luz sobre importantes problemas culturales y políticos que afectan a América Latina.

En el siglo XVI, Sevilla era el principal punto de acceso al comercio transatlántico del Imperio Español, gracias a su posición como el único puerto fluvial de España y por ser una de las ciudades más grandes de Europa Occidental. Por ello, considero que la elección de Sevilla como sede de esta exposición es significativa, ya que revitaliza el papel histórico de la ciudad como punto de conexión y destaca los profundos lazos culturales entre España y América Latina.